A Bit of Legal History: Why Are There Words of French Origin Used in the Modern Practice of Law in the US?

Introduction

“Law French was like a hyphen that kept alive the general framework of an earlier vocabulary and syntax until a time when English had become a full and flexible language and had appropriated the necessary French elements, expressions, and vocabulary.”

--Caroline Laske

Anyone who has studied or practiced law in the United States is aware that this country’s legal heritage is primarily English—that is, English colonists transferred the English common law tradition to the United States—and with it, stare decisis, a Latin term meaning “let the decision stand.” As Latin had long been used in England for legal documents, Latin also arrived with colonial English jurists. Many of these Latin terms—e.g., amicus curiae, certiorari, de jure, de novo, and dictum, are still used in modern law practice in the United States. However, what about the terms that are seemingly French in origin—e.g., force majeure, voir dire, replevin, escheats, etc.? How did those terms enter the legal lexicon of the common law tradition?

The answer to this question is complex but generally harkens back to the Norman Conquest of England, which began in earnest with the 1066 Battle of Hastings led by William the Conqueror. The term “Normans” is used to describe the inhabitants of northern France who were originally Scandinavian (Northmen) but hitherto lost their national identity becoming French, both culturally and linguistically.[1] As a result of the Normans’ victory in the Battle of Hastings, the Anglo-Saxon ruling class in England was replaced by William’s noblemen who spoke a Norman French dialect.

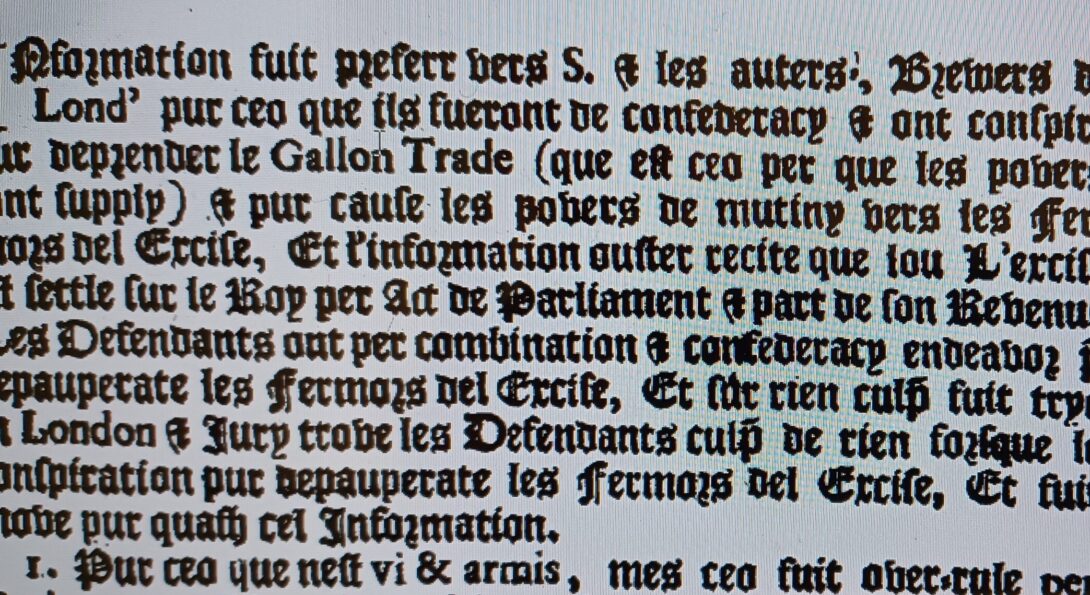

After several centuries of Norman rule in England, a highly specialized legal language based on Norman French (“Law French”) emerged and became the language used for official documents, legal tracts, treatises, and statutes, although there is no evidence Law French was spoken in English courts.[2] The transition from Latin to French, at least in written form, developed over time and, according to Caroline Laske, “In all probability, French was the most convenient and practical language to use. Latin, though the language of the learned, was rigid and archaic and lend itself not necessarily well to be adapted to the new situations of an evolving society and legal system.”[3]

Law reporting continued in the language of Law French in England until the 17th century as the quotidian Norman French dialect began to give way to English. However, some words and phrases of Law French lingered and remained in the English jurist’s lexicon—eventually making their way in the 17th century to what were then the thirteen colonies.

For more on this fascinating topic, see the Manual of Law French, which is shelved in the UIC law library’s reference section on the 6th floor at KD313 .B34 1990. Digitized court reports written in Law French are available in HeinOnline in the “Selden Society Publications and the History of Early English Law” database.

[1] M.E. Alexeyev et al., “Law French in Legal English: Emergence, Evolution and Reasons for Vitality,” 2 Тrаnscarpathian Philological Studies 249, 251 (2022), http://zfs-journal.uzhnu.uz.ua/archive/25/part_2/45.pdf.

[2] Caroline Laske, "Losing touch with the common tongues – the story of law French," 1 Int’l J. Legal Discourse 169, 179 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/ijld-2016-0002.

[3] Id. at 180.