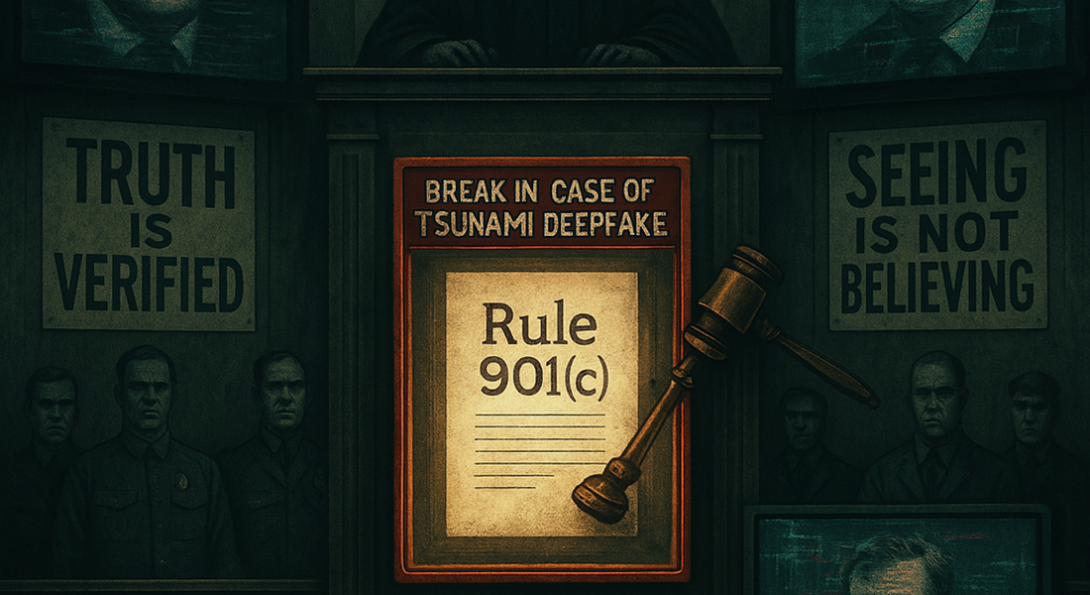

A Deepfake Evidentiary Rule (Just in Case)

A useful evidentiary provision awaits for rapid implementation if any deepfake problems arise.

The legal profession has been anticipating a "tsunami of deepfake evidence"[1] dropping into exhibit lists.[2] A 2023 New York Times article revealed that the widespread availability of free or inexpensive apps for creating deepfakes makes it alarmingly easy to manipulate digital evidence.[3] Three methods have been developed to address deepfakes: technical experts, procedural reviews, and evolving court rules.[4]

First, digital forensic experts utilize advanced machine-learning techniques and multimodal analysis to determine the authenticity of digital media, particularly challenging deepfake videos while navigating the complexities of digital manipulation to uphold the integrity of the justice system.[5] Second, courts will continue to rely on existing rules to adjudicate cases involving digital evidence, creating challenges related to the burden of proof and the costs associated with verifying the legitimacy of such evidence, particularly in criminal and civil contexts, as rising deepfake technology complicates the legal landscape.[6] Finally, federal courts are deliberately moving to address deepfake evidence. At a meeting on November 8, 2024, the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules ("Advisory Committee") considered proposed Rule 901(c). The rule would govern “potentially fabricated or altered electronic evidence.”[7]

As a threshold, deepfakes present an authentication issue. According to Weissenberger's Federal Evidence, Rule 901(b)(9) likely serves as the basis for the authentication of various types of computer-generated evidence; however, deepfakes were not the sort of computer-generated evidence contemplated.[8] Some judges acknowledged that deepfakes seeped into family court proceedings; for example, a party might produce an AI-generated cellphone recording of their spouse to win custody of their child.[9] At this point, the federal cases addressing deepfakes were truly fabricated audio or video recordings.[10]

The proposed amendment introduces a new section specifically addressing deepfakes and clarifying the burden of proof for evidence suspected of being altered or fabricated (in whole or in part) by AI.[11] A major issue with AI-generated deepfakes is their ease of creation and difficulty in detection. Authenticity is typically governed by a low standard of admissibility under Rule 901(a): evidence that is sufficient to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it to be.[12] For the moment, the Advisory Committee remains cautious on an amendment to Rule 901 to address deepfakes, reasoning that in "the few cases where deepfake issues have arisen, courts have generally been able to address them under the existing rules governing authenticity."[13]

Nevertheless, the committee will develop rule language to assist courts in reviewing deepfake claims if existing rules are insufficient.[14] The committee recognized that technology evolves rapidly, and the rule-making process is slow.[15] Accordingly, the committee sought to refine a potential amendment and deploy it as necessary; at that point, the rule would be ready for implementation without delay.[16]

The committee opined that the proposed rule would be based on two principles.[17] First, an opponent should not be allowed to initiate an inquiry into whether an item is a deepfake simply by claiming it is one; a preliminary showing of evidence suggesting the item might be a deepfake should be required.[18] Second, if the opponent does provide evidence indicating that the item may indeed be a deepfake, the opponent must prove the authenticity of the item using a higher evidentiary standard than the usual prima facie standard typically applied under Rule 901.[19] The working draft of a new Rule 901(c) provides the following:

Potentially Fabricated Evidence Created by Artificial Intelligence.

- Showing Required Before an Inquiry into Fabrication. A party challenging the authenticity of an item of evidence on the ground that it has been fabricated, in whole or in part, by generative artificial intelligence must present evidence sufficient to support a finding of such fabrication to warrant an inquiry by the court.

- Showing Required by the Proponent. If the opponent meets the requirement of (1), the item of evidence will be admissible only if the proponent demonstrates to the court that it is more likely than not authentic.

- This rule applies to items offered under either Rule 901 or 902.[20]

As suggested above, the proposed rule utilizes a burden-shifting mechanism requiring the opponent of evidence to provide sufficient information for a reasonable jury to find fabrication under Rule 104(b) before shifting the burden to the proponent of the evidence to show that it is genuine by a preponderance of the evidence pursuant to Rule 104(a).[21] The committee also noted a preference for tailoring the draft provision to an “item of evidence” that has been fabricated by “generative artificial intelligence” because generative artificial intelligence (GAI) is capable of creating such fake evidence.[22]

The committee decided not to issue a publication for notice and comment and agreed to keep proposed Rule 901(c) on the agenda for its fall 2025 meeting.[23] In making this decision, the advisory committee noted that there was less need to invite public comments on the deepfake issue, and a useful provision was created for rapid implementation if any problems arise.[24] The Advisory Committee’s report on proposed Rule 901(c) was included for consideration by the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure[25] at its June 10, 2025, meeting.[26]

[1] Deepfakes are multimedia files that imitate real or fictional individuals, making them appear to say or do things that never happened. Kohls v. Ellison, No. 24-cv-3754, 2025 WL 66765, at *1 (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025). They utilize advanced AI algorithms for manipulating a person's likeness, voice, or actions, making it challenging for most people to identify fakes. Id.

[2] Chuck Kellner, The End of Reality? How to combat deepfakes in our legal system, A.B.A. J. (Mar. 10, 2025), https://www.abajournal.com/columns/article/the-end-of-reality-how-to-combat-deepfakes-in-our-legal-system.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Weissenberger’s Federal Evidence, § 901.41 (8th ed. 2024) (noting that computer-generated evidence has been used to re-create airplane accidents, to re-enact automobile accidents, to assess the fair market values of property interests, and to construct hypothetical markets in antitrust claims, as well as to serve as evidence of computer-related crimes and evidence of electronic contracts).

[9] Jack Karp, AI Deepens ‘Quicksand’ Landscape for Evidentiary Measures, Law360Pulse (Apr. 16, 2025), https://www.law360.com/pulse/articles/2320591/ai-deepens-quicksand-landscape-for-evidentiary-measures.

[10] Broadrick v. Gilroy, No. 24-cv-1772, 2025 WL 1669361, at *3 n.1 (D. Conn. (June 13, 2025) (including claims related to allegations of creation and publication of deepfakes); Doe One v. Nature Conservancy, No. 24-cv-1570, 2025 WL 1232527, at *1-3 (D. Minn. Apr. 29, 2025) (addressing a false light claim involving AI-generated images); League of Women Voters of New Hampshire v. Kramer, No. 24-cv-73, 2025 WL 919897, at *1 (D.N.H. Mar. 26, 2025) (addressing robocalls using an AI-generated deepfake voice technology to mimic President Biden's voice to suppress Democratic voter turnout); Project Veritas v. Schmidt, 125 F.4th 929, 954–55 (9th Cir. 2025) (discussing unauthorized voice recordings to create deepfake audio files); Kohls v. Bonta, 752. F. Supp. 3d 1187, 1191 (E.D. Cal 2024) (involving videos containing demonstrably false information, including audio or video significantly edited or digitally generated using AI).

[11] William M. Carlucci, Kaitlyn E. Stone & Nicholas A. Sarokhanian, Changes Proposed to the Federal Rules of Evidence to Address AI Usage, Barnes & Thornburg (Nov. 15, 2024), https://btlaw.com/en/insights/alerts/2024/changes-proposed-to-the-federal-rules-of-evidence-to-address-ai-usage

[12] Comm. on Rules of Prac. & Proc., Agenda Book, 59 (June 2025), https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/document/2025-06-standing-agenda-book.pdf [hereinafter Agenda Book].

[13] Id. at 60.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at 98.

[22] Id. at 97.

[23] Id. at 97, 99.

[24] Id. at 98.

[25] The Rules Committee is an advisory body to the Judicial Conference of the United States. About the Judicial Conference of the United States, United States Courts, https://www.uscourts.gov/administration-policies/governance-judicial-conference/about-judicial-conference-united-states#organization (last visited June 26, 2025).

[26] Agenda Book, supra note 12, at 59–62, 98–99.