Dr. King’s Chicago Campaign & Legacy for Fair Housing

Dr. King's Chicago campaign aimed to address housing discrimination through direct action and advocacy, ultimately contributing to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Weeks after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s southern field staff moved to Chicago's Near West Side to launch what would become known as the Chicago Freedom Movement.[1] The Movement had a broad agenda, including organizing for better schools, organizing on the West Side, launching the End-the-Slums campaign, and developing Operation Breadbasket.[2]

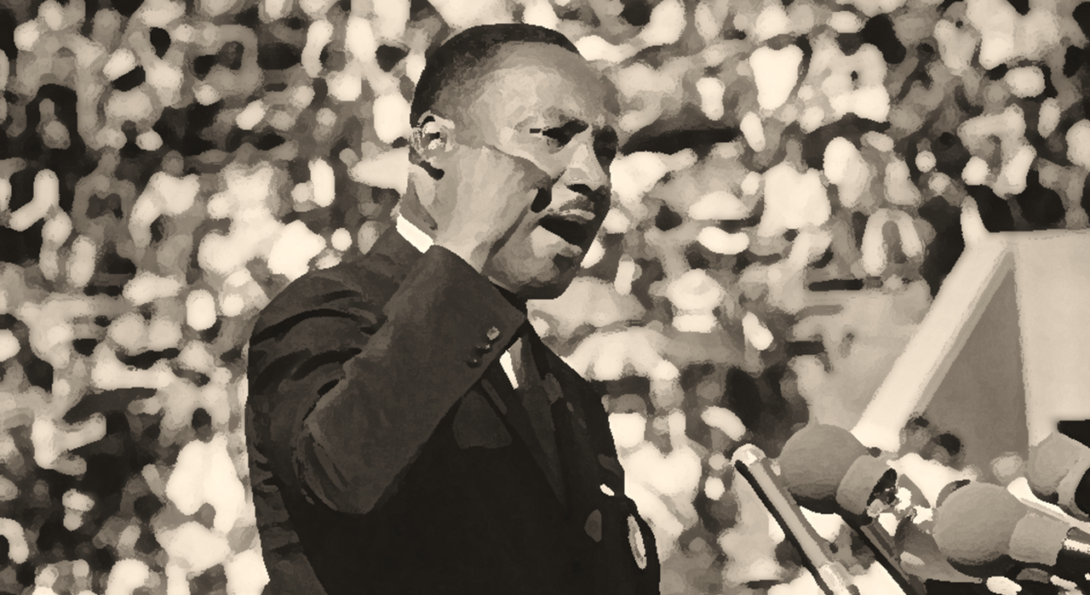

By the spring of 1966, the Movement had targeted housing discrimination for its summer direct action plan.[3] The direct action campaign kicked off on July 10, 1966, where “more than 30,000 supporters flowed into Soldier Field for a rally and then a march to City Hall.”[4] At City Hall, Dr. King posted a long list of demands on the door, including the Movement’s primary target: housing.[5] A week later, open-housing marches commenced in Chicago, which resulted in the “Summit Agreement,” wherein the City of Chicago pledged to work towards open housing.[6] Significantly, it also spurred the creation of the Leadership Council for Metropolitan Open Communities, an organization dedicated to promoting fair housing in the Chicago metropolitan area.[7]

Commenting on the Movement, Jesse Jackson proclaimed: “If out of [the Chicago Freedom Movement] came a fair housing bill, just as we got a public accommodation bill out of Birmingham and a right to vote out of Selma, the Chicago movement was a success, and a documented success.”[8] However, federal fair housing legislation floundered even after President Lyndon B. Johnson called for Congress to expand on existing civil rights laws.[9]

To some, President Johnson appeared to be walking a fine line between supporting civil rights while avoiding the impression that civil rights leaders overly influenced him.[10] Moreover, President Johnson privately opposed the Movement’s marches and the corresponding violence they provoked.[11] Of course, President Johnson was not beneath exploiting acts of violence for political expediency.[12] In this case, President Johnson did not want to leverage police violence against the Movement activists, as it could alienate or embarrass his ally in Chicago, Mayor Richard J. Daley.[13]

Another sticking point arose as tensions developed between President Johnson and Dr. King due to Dr. King’s criticisms of President Johnson’s handling of the Vietnam War.[14] President Johnson only began pursuing the passage of fair housing legislation in earnest when the Movement disbanded after the Summit Agreement was made, and Dr. King left Chicago to pursue other initiatives.[15] In the congressional trenches, Senators Edward Brooke and Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts engaged in significant debates, advocating for the passage of this legislation.[16] Senator Brooke, the first African American to be elected to the Senate by popular vote, spoke personally about his return from World War II, expressing his frustration at being unable to provide a home of his choice for his new family because of the discrimination he faced due to his race.[17]

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King’s life ended. His assassination silenced the strongest American voice for nonviolent change, creating a significant gap in the fight for racial equality and economic justice, which led to widespread social unrest and highlighted the urgent need for a more just society. Once again, violence spurred change in the United States. The swift political response was symbolic and practical.[18] The nation mourned a collective loss, leading to congressional action as a unifying statement.[19] In the aftermath of the assassination, violence erupted in African American communities across several cities, prompting some members of Congress to believe that a legislative response could address the underlying frustrations and restore order.[20] President Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law on April 11, 1968.[21]

To say that the Fair Housing Act has impacted many of our law school’s students (past and present) would be an understatement. Our law school is unusual in that, from the outset, “admission to the school should not be determined by ‘arbitrary and discriminatory factors such as racial origin, sex, color, nor religious affiliation.’”[22] Few law schools have fair housing clinics, and our law school’s Fair Housing Legal Support Center & Clinic might be described as peerless. Through the efforts of the directors, clinical professors, staff attorneys, testing coordinators, grant administrators, support staff, and so many students in the Center & Clinic, our law school has honored Dr. King’s legacy as an enduring force in the battle against housing discrimination in Chicago, throughout Illinois, across the nation, and even globally.

For more information, visit the Fair Housing Legal Support Center & Clinic’s website and the UIC Law Library’s research guide on Fair Housing Law.

[1] The Chicago Freedom Movement 13 (Mary Lou Finley et al. eds., 2016).

[2] Id. at 16, 22, 24, 36.

[3] Id. at 44.

[4] Id. at 45.

[5] Id. at 45–46.

[6] Id. at 51, 63–65.

[7] Id. at 67. The Leadership Council for Metropolitan Open Communities partnered with the John Marshall Law School in 1985 to develop an "in-house program to train law students in the practice of fair housing law and to offer free legal services to victims of housing discrimination." Id. at 220. For more than thirty years, our law school’s Fair Housing Legal Support Center & Clinic has been dedicated to educating the public about fair housing law and providing legal assistance to private or public organizations that seek to eliminate discriminatory housing practices.

[8] The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North, Project Muse, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/185/edited_volume/chapter/1766743 (last visited Apr. 3, 2025) (transcribing The Chicago Freedom Movement—Activists Sound Off, Chi. Pub. Radio (Aug. 23, 2006), https://www.wbez.org/eight-forty-eight/2006/08/23/the-chicago-freedom-movementa-activists-sound-off.

[9] The Chicago Freedom Movement, supra note 1, at 117.

[10] Id. at 119.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. President Johnson condemned police violence in Birmingham and Selma to ensure passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, respectively. Of course, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy also provided impetus for the passage of the Civil Rights Act. See Michael P. Seng & F. Willis Caruso, Forty Years of Fair Housing: Where Do We Go from Here?, 18 J. Affordable Hous. 235, 235 (2009).

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at 121.

[15] Id. at 123.

[16] 44th Anniversary of Fair Housing Act, Fair Hous. Project (Apr. 10, 2012), https://www.fairhousingnc.org/2012/44th-anniversary-of-fair-housing-act/. HUD used to have a section on the History of the Fair Housing Act, but it has been removed.

[17] Id.

[18] The Chicago Freedom Movement, supra note 1, at 124.

[19] Id.

[20] The Chicago Freedom Movement, supra note 1, at 124–25.

[21] 44th Anniversary of Fair Housing Act, supra note 16.

[22] William Wleklinski, A Centennial History of The John Marshall Law School 10 (1999).